On Founder Taste

I. WWSJD (What Would Steve Jobs Do?)

Imagine you're a 22 year old young buck, fresh out of Stanford-Harvard-(insert elite credential here), with just enough friends and family money to insulate yourself from having to work for someone, but not enough that you can spend the next 20 years being the Dan Bilzerian of Silicon Valley. The obvious next step, after having spent most of your 22 years on this Earth checking boxes on some self-imposed track to be a Billionaire—though you've yet to conceive a fundamental Good to orient yourself and all that hypothetical capital towards—is to loosen the shackles of conformity and showcase your inner original by starting a tech startup. All the cool kids are doing it, but you're not like them. Your startup will be different because you're different. You are, as your friends like to say, a contrarian. Great! Now what should you build?

How about reinventing the future of work by leasing out entire floors in office buildings and renting them out at premium to millennials and zoomers? Shit, looks like that grift's been done already. Ok, how about a mattress company? Not too hot either? Alright, let's try...a looping video app for hot teens! Like YouTube, but mobile-first! Nah, you're right, there are already a shit ton of platforms lining up to turn women into subscription bundles so as to increase market share in a saturated media economy just to sell ads to a generation that will die with less wealth than its parents. Hmm, this is harder than it looks, huh.

Not really, just dress the part...

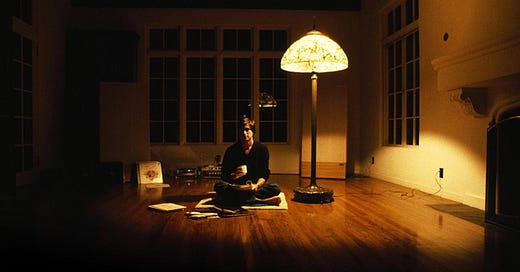

Let's forget you for a moment. This might help instead: if he were around today, what would a 21-year old Steve Jobs choose to build? Based on the man's mono-maniacal ambition, and his oft-quoted desire to "make a dent in the universe", we can be sure that his standard for opportunities worth pursuing would be astronomically high. It wouldn't be something as trivial as any of the above, but it also probably wouldn't be as obvious as the juvenile, techno-deterministic ideas one would find in an episode of The Jetsons. It would be impressively challenging and technological novel, no doubt, but grounded in some culturally relevant dimension. That was Steve. But given the startup world's most visible and lauded output of late (Clubhouse, Superhuman), it is doubtful a 21-year old Steve Jobs would even consider starting a company in 2020. Why? He probably wouldn't even get funded.

II. The Taste Imperative

Here's the reality: there is no shortage of hard as fuck, hair on fire, existentially important problems to solve in our world today. Just take a cursory look outside and you'll get the picture. Yet, if we were to judge by Silicon Valley's record over the last decade, one would assume we have reached the End of History, and all there is left to do is alternatively amuse ourselves to death, work ourselves to death, or share a ride with a stranger on our way to amusing/working ourselves to death. *there’s one exception, but we’ll get to that

This is reflected in the fact that the most successful American IPOs in tech over the last decade, post-Facebook, have been Uber and Snap. Though decidedly ambitious, Uber, as a commodity cab on demand service, is far from a cure for cancer, and has caused its fair share of controversy. As Alex Danco put it, though it appears novel, Uber is still fundamentally anti-progress:

It’s still the same car, and it still needs a driver. It moves the same speed, burns the same gas, and gets stuck in the same traffic. What has actually changed?

Snap, with its jovial social thesis, arguably owes its success mainly to porn stars and hormonal teens. Still, none of that derailed these companies off of their hype train—until they had to kiss the ring of the public markets. Indeed at time of writing, Snap has not traded above its opening day price since the IPO, and Uber’s own IPO was a major disappointment right out of the gate. Shares peaked at $45 and trended down before closing at $41.60/share. As I write this, Uber is now trading at just $29 per share. What goes up...

Now to that exception I mentioned above: when we stretch back our timeline to 2010, before Facebook's IPO, we find that the most successful American tech company to go public was none other than Elon Musk's Tesla Motors, which has, at time of writing, surpassed Toyota to become the most valuable car company in the world. In fact, Tesla's IPO was the first one from an American car company since Ford. It wouldn't be unreasonable to say that Tesla—with its mission to "accelerate the world's transition to sustainable energy"—is the most difficult startup ever attempted this century, given the fact that there's been no successful American car startup since Chrysler over 90+ years ago. Scratch that, it would be the second most difficult startup attempted this century; the first is obviously SpaceX, a literal private space program attempting to build colonies on Mars by century's end. Its founder? Also Elon Musk.

In other words, the two greatest startups (great measured here in a startup's success relative to the difficulty of its task) founded this century were also the two most high impact, highly challenging, and most likely to fail projects attempted. What does this tell us?

For one, with a failure rate close to 90%, all startups are incredibly hard to pull off. Deciding to build an "easier" startup like a mattress company, a chat app, or a glorified email client for rich people is a futile endeavor. At best, you create marginal value because you're solving trivial problems. At worst, you actually destroy value because your startup sucks up capital and talent that could have gone to more ambitious projects, assuming you don't crash and burn before it comes to that.

There's a corollary here, which is that founders are the single greatest determinants of a startup's success or failure strictly for one reason: the very act of choosing what to work on effectively seals a startup's trajectory. Great founders don't just solve problems. Great founders know how to find the problems worth solving in the first place.

Bezos was not the only person to surmise, as he did, that the internet was growing at a rate of 2300% per year. He was, however, the only one who thought to build an all-encompassing store on top of this new platform. It wouldn't be a stretch to say that probably 90% of all the value created by a company is found in choosing what opportunities are worth pursuing, and the skill required to do that is fundamentally a matter of Taste.

Here's what Steve Jobs had to say about this:

People think focus means saying yes to the thing you've got to focus on. But that's not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully. I’m actually as proud of the things we haven’t done as the things I have done. Innovation is saying ‘no’ to 1,000 things.

— Steve Jobs

Taste is easily defined as the ability to discriminate between the valuable and the expandable. It’s another word for Good Judgment. When you decide whether to eat sushi or calamari for dinner, you're in fact erecting a hierarchy of value, and passing judgment according to said hierarchy. If you choose sushi, that is because you've deemed it best for dinner. It is reflective of your culinary taste. Similarly, when you decide that X is a better problem to attack than Y, you are creating a hierarchy of problems in the world and displaying your judgment in sorting it out. This is your Founder Taste.

To put it bluntly, a Founder's Taste makes or breaks his company because the startup's potential expands or shrinks in proportion to the problems it chooses to tackle.

This idea of Taste is an interesting concept brought up by OpenAI's John Schulman, referring to the fact that great researchers have an equally great nose for what problems to work on:

Your ability to choose the right problems to work on is even more important than your raw technical skill. This taste in problems is something you’ll develop over time by watching which ideas prosper and which ones are forgotten. You’ll see which ones serve as building blocks for new ideas and results, and which ones are ignored because they are too complicated or too fragile, or because the incremental improvement is too small.

Unlike researchers' problem taste, which focuses mainly on the strategic, Founder Taste also has a deep societal dimension because startups actively reshape the world around us. There are two components to Founder Taste: 1) Strategic (what to work on); 2) Cultural (how what I’m working on touches people). Few Founders nail both, but all great founders master at least the first one.

Judging by the current state of technological stagnation in the developed world, and the overall state of startups and the backlash against them, it is clear that most founders in Silicon Valley today have a profound lack of Founder Taste. It isn't enough to just build stuff people want. This is the First commandment of the startup world today, and it has given us the Lean Startup school of mediocre products and led us down a path of trivially inconsequential drivel which only serves to, again, help the common man amuse himself to death as the real world disintegrates around him. There is more to life than pure, unadulterated consumption. There are things we can build that actually improve people's lives—new housing, new energy modalities, uplift millions of poor people across the developing world. We don't want to "feel good". We want to be good. More than ever, founders need to learn how to build things people didn't know they needed. This skill is more an art than science.

Like Jobs before him, Elon is the single most celebrated founder of our era precisely because his remarkable Founder Taste fulfills both the strategic and cultural criteria. His portfolio of projects, the majority of which are atoms-first—not software—is a testament to that.

Tesla's cars are some of the most beautifully crafted vehicles on the road today. The spell-binding ballet of SpaceX' Falcon heavy engines engaged in synchronized landing has brought joy to thousands of people. Like Jobs, Elon understands the cultural, aesthetic value of the grandiose gesture.

Thus Founder Taste is not simply about having a nose for the right things to work on, but also this classic notion of taste itself—the cultural element which ensures startups can adequately solve the problem they are tackling by anchoring their company within the communities it serves.

This, ultimately, was Steve Jobs' greatest strength, and the reason why he, more than rain-makers like Gates or Bezos, is the archetype for the legendary startup founder.

What Jobs is referring to is the fundamental difference between "builders" and craftsmen, or why even though engineering builds, it is design which establishes. Essentially, products—no matter if they're technological in nature or not—do not exist in a vacuum. On the contrary, every single product worth its salt is designed to exist within a societal (cultural) context. It will be played with, re-contextualized, used, shared, spoken about, derided, etc. In other words, all products inevitably become cultural artifacts.

What that means, fundamentally, is that far from existing outside of it, Technology, like art, is in fact also a cultural activity. And in order to create technology that fits or elevates the cultural context (utopia) rather than degrades or debases it (dystopia), Jobs believed that great companies (and by extension, great founders) must have a heightened sense of Taste. Indeed, Jobs' dig at Microsoft was not at the company at all, but at his frenemy, Bill Gates, whose archetypal nerdiness has always belied a deep lack of taste. Thankfully for Gates, his nose for problem-finding was unmatched. But it is no coincidence that it was Jobs who, having come back to his empire, built the iPhone and catapulted Apple beyond every other company in the world while Gates-Ballmer had to play catch up.

III. Developing Taste

By now, you probably wonder how one goes about developing so-called Founder Taste. It feels ineffable, like some elusive Platonic form. In truth, it's actually quite simple. You develop your taste like you develop any skill: through imitation, repetition, experience, and feedback. Tactically, taste is a matter of repetitive exposure to Excellence. What's Excellence? You will know it when you see it. Like Beauty, Excellence cannot be rationalized; it merely commands your surrender through awe.

Once again, Jobs comes to our rescue:

Ultimately, it comes down to taste. It comes down to trying to expose yourself to the best things that humans have done and then try to bring those things into what you’re doing. Picasso had a saying: good artists copy, great artists steal. And we have always been shameless about stealing great ideas, and I think part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians and poets and artists and zoologists and historians who also happened to be the best computer scientists in the world.

— Steve Jobs

Notice the emphasis on the diversity of interests. Dedicating yourself to exposure to excellence is bound to take you through a broad range of fields: from philosophy, to the arts, to history, and back again to science and technology. It's not a coincidence that the civilizational peak that was the Renaissance also saw the proliferation of polymaths. Michelangelo wrote excellent poetry, alongside being the greatest sculptor of all time, and a painter second only to Raphael.

Ultimately it is this broad-mindedness which made Jobs so irresistible to both the tech world, and the world at large. Compared to the Borg-like Gates, Jobs appeared at once human and superhuman. Sure, the Apple II was Woz' invention, but Apple itself was Jobs' great work of art. And it was his Taste which enabled him to reach such heights.

The great redeeming quality of Silicon Valley is that it celebrates and borderline deifies its mythical founders. In doing so, the valley generates these archetypes of Excellence that future founders can strive to emulate, match, and potentially, exceed—first by imitating the great, then by seeking greatness for themselves. This is how you develop your taste. The way to exceed Steve Jobs is not to wear a black turtle neck as well and talk lavishly about changing the world. The way to exceed him is first to understand what it is that made his work great, to develop an appetite—and commensurate confidence—for outsized ambitions, and finally to be fearless in your pursuit of greatness and excellence.

Indeed this deep ambition is implied within the umbrella of Founder Taste. As Napoleon said,

Great ambition is the passion of a great character. Those endowed with it may perform very good or very bad acts. All depends on the principles which direct them.

Most founders today think they are ambitious. Every one of them believes that their personal CRM startup is somehow going to be instrumental in achieving world peace. But this is not ambition. Ambition is not the profession of a great goal; it is, as Napoleon stated, a personal resonance, a burning Will to achieve a thing. It's unmistakable, and usually unique to the individual possessed by it. Poll any person on the street, and almost nobody would argue against the idea of world peace. But the person who's possessed by this idea, and spends nights and days plotting, planning, and scheming a solution with this one end in sight, that person is to be paid attention to, maybe even feared, and eventually, if they succeed, admired.

A world where exponentially more founders have tremendous Founder Taste is one with a lot more Tesla’s and SpaceX's, and less vaporware like Magic Leap or WeWork. Not all startups are created equal, and there are hierarchies of problems worthy of being solved. In order to create true wealth, founders need to develop their taste, and graduate from the comfortable fantasy of changing the world from their bedroom with one line of code. We are not at the beginning of the web anymore. Such spaces are claimed. Instead, founders should think about leveraging startups’ greatest qualities to attack the tremendous challenges afflicting us in the real world—the world of atoms.

If you're a young founder reading this, the basic take-away is that you should be biased against starting a new company—especially if it's pure software. Sure, build your muscle for building by creating things and trying stuff out. But company formation itself should be a rare act. There are arguably only 2-3 companies every decade who actually matter. Instead of coding up a thoughtlessly designed tool and throwing it at the world to digest, you should instead spend that time to hone your Taste and mold yourself into an exception. Only then will the world's secrets reveal themselves to you. And when they do, you may at last be worthy enough to change it.